For years, George Washington University has told families that it observed a need-blind admission policy. Students were accepted regardless of their ability to pay.

GW’s student newspaper wrote an excellent article this week that revealed that the university’s stated need-blind admission policy was actually a need-aware practice. The university admitted that it put hundreds of students on its wait list every year because they wouldn’t be able to pay GW’s tuition. The school estimated that up to 10 percent of the school’s roughly 22,000 applicants fall into this category.

In GW’s case, the school looked at applications without regard to need in the first round. Before the freshmen class was finalized, however, the school took a closer look at the applicants who had received initial approval.

Need-Aware Admission Policies

I am bringing this up today because GW’s admission policy is similar to countless schools that mainly depend on their tuition revenue to pay the bills. These schools need a healthy percentage of students who can pay the full tab or a good portion of it (minus one of those ubiquitous merit scholarships), which helps subsidize the costs of middle-class and low-income student who require a lot of financial aid.

Many schools will admit the majority of their students without regard to need, but the last 10%, 20% or 25% will be determined by their ability to pay. I like to call this affirmative action for the rich. I’d argue that affirmative action for the wealthy is far more prevalent than affirmative action for minorities.

Another Need-Aware Example

Reed College, an elite liberal arts college in Portland, OR, provides what is probably the most well-publicized example of a need-aware policy. Back when the country was in the grips of the recession in 2009, the school faced a returning student body that needed more aid and the freshmen class was also needier.

Reed’s financial aid office looked at the list of accepted freshmen (acceptances letters had not been sent out yet) and told the admission department to kick more than 100 students off the list that needed aid and substitute them with affluent students who could pay the full price.

Due to budget realities, schools across country give breaks to wealthy students admission breaks, but in this case a New York Times reporter was in the room and wrote this front-page story about Reed’s decision that generated a firestorm of anger.

Protecting Yourself Against a Need-Aware Practice

The best way for a teenager to protect him/herself from being a casualty of a need-aware system is to be as attractive an applicant as possible. It’s often student with high need who are in the bottom half of the applicant pool who are going to get denied, waitlisted or accepted via a practice called admit-deny. Here is how admit-day works: a school will accept applicants with high need, but give them such lousy financial aid packages that they can’t attend the school.

Also remember it’s meaningless if a school says it’s need blind (it accepts students without any regard to need) in admissions, but provides mediocre financial aid to students who need substantial help with the tab. To it’s credit, Reed is one of just five or six dozen schools that meets 100% of all its students’ financial need, but GW and nearly all other colleges and universities don’t.

How Truthful are Schools?

GW is on a roll because this is the second time in less than a year that it’s been embarrassed by its own disclosures.

Last fall U.S. News & World Report punished GWU, which had been ranked the 51st best national university, after the school admitted that it had been fudging the percentage of freshmen who were in the top 10% of their respective high school class. In essence, the school was looking more selective than it really was and the false reporting had been happening for more than a decade.

And that leads me to the other reason why I shared GW’s story today. As consumer, you have to be careful about what a school says. You can’t assume that what you are hearing from an admission office, which serves as a school’s institutional cheerleaders, will always be truthful.

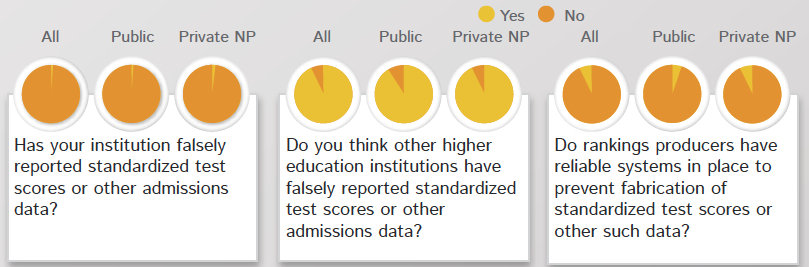

To back up what I’m saying, I am sharing two statistics from the most recent Gallup survey of senior admission officers that was sponsored by Inside Higher Ed, a respected trade publication that I read every day.

The survey asked schools whether they have ever falsified standardized test scores or other admissions data. Only 1% of schools admitted they had.

But here is the more interesting question: Do you think other higher education institutions have falsely reported standardized test scores or other admission data?

Ninety three percent of admission administrators answered yes.

Lynn,

If a college can’t afford to meet the full-need of all students and also be need-blind in admissions, what do you think that they should do to stay afloat? I think that schools like Reed who would like to be need blind, but just can’t afford it, should be commended for their open and honest disclosure of their policies. Where I have issue is when schools are dishonest, like I suppose George Washington has been. I am still not a skeptic. I believe that most of the schools who profess to be need-blind in admissions are. Just because a few bad apples aren’t honest, doesn’t mean the rest of the need-blind institutions are also lying. Am I just naive? My own sons were accepted to need-blind and meets-full-need schools, and they had financial need. And they weren’t curing cancer or olympic athletes in high schools by any stretch. I’ve asked so many admissions reps about this, people I respect, and I’m just not convinced. Do you think I’m gullible?

Hi Karen,

I agree that it’s best when schools are honest with families and explain that they are need-aware institutions. Unfortunately, there is a lot of deception in the higher-ed world as schools are focused on putting together a freshmen class every year. The longer that I’ve been writing about college, the more cynical I have become about this industry — and it is an industry.

I am skeptical that most schools that say they are need-blind really are. If they were strictly need blind, why are the vast majority of students accepted to elite schools affluent? You think there would be some fluctuations year to year. Also elite schools can set their standards so high that the students who can jump these hurdles are primarily going to be wealthy. Schools can find out a lot about students just by looking at their applications such as where parents attended college and what are their occupations. Why in the world would schools need that information except to get a better sense of the financial situation of a student.

Lynn O’Shaughnessy

The senior admissions/financial aid executive at Muhlenberg College (PA) actually told a large audience of parents (and me) that the school was need-aware.

He didn’t use that term, but he explained that a student who ranked in the upper 10th of the pool would receive a package to fulfill need that was weighted more heavily to scholarships and grants while a student who ranked in the bottom 10th would receive a package that was weighted more towards self-help aid (the Stafford Loan and Work-Study).

In addition, he offered families interested in Early Decision an opportunity to have an “early review” of their prospects for need-based and merit-based aid based on the CSS, the tax return and the student’s academic record–before they started the application for admission! The college has an early decision deadline of February 15th; serious families have time to get the early review, apply or pass, if they don’t like the results.

Thanks Stuart. Actually, Muhlenberg has a frank essay on its site that explains the reality of need-based aid. Here is the link: http://www.muhlenberg.edu/main/admissions/therealdealonfinancialaid/

Lynn O’Shaughnessy

I would just like to add that the list of accomplishments correlated with affluence that colleges use as proxies to determine the financial resources of their applicants is much longer than the few examples I included above.

The percentage of full-pay students at these schools barely changes from year to year. Pretty neat trick for a supposedly need-blind school to pull off.

Need-blind is a myth, everywhere. The elite schools that are supposedly need-blind and meet all required need use other admissions hurdles to make sure they get the number of full pay students they desire.

What is the difference between being need-aware and requiring accomplishments of a certain percentage of its applicants that are nearly unheard of outside the families of the affluent?

What is the difference between being need-aware and holding a large number of admission slots for HS students who have: started their own charities, done actual scientific research, succeeded in academic Olympiad competitions that require years of prep/guidance and that the vast majority of HS students have never heard of, etc. ???

The only effective difference between GWU and Harvard is that, due to its relative prestige, Harvard does not have to measurably compromise its academic standards to get the percentage of full-pay students it desires. There are enough top-tier applicants to mask the fact that it, like all schools, is extremely need-aware, thus giving it the cover it needs to make the insincere marketing claim that it is need-blind.

I completely agree with you JD. Even without setting the requirements so high that only very wealth students can meet them, schools discover a tremendous amount students without them ever applying for financial aid. Schools have many ways of telling whether a student’s parents are rich without ever asking the question.

Lynn O’Shaughnessy

JD is spot on. Heck, a school that looks for high SAT scores has a remarkably effective way of weeding out poorer students, since those scores are a terrific proxy for family income.