Are you wondering if your child will someday win an athletic scholarship?

Some of the parents who are dreaming of sports scholarships have children who are only in grade school and middle school. Even my own sister, whose daughter is 12, believes that a soccer scholarship is in her future.

Even my own sister, whose daughter is 12, believes that a soccer scholarship is in her future.

The reality is that athletic scholarships aren’t nearly as plentiful or as lucrative as many families assume. About 2% of high school seniors win sports scholarships every year at NCAA institutions.

Athletic scholarships are typically not as generous as regular financial aid or merit scholarships that student athletes can earn.

Whether your child will qualify for scholarship money will depend on many factors. What follows are some of the things that you need to know about athletic scholarships.

Understand Where the Money Is

There are six NCAA sports where athletes have the best chance of receiving a full-ride award. They are found within the Division I schools, which tend to offer the biggest sports programs or which aspire to have a national reputation.

A full-ride scholarship in the NCAA system covers tuition and fees, room, board and required course-related books.

Head-Count Sports

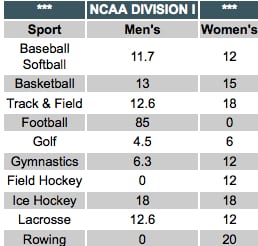

The best chance for a full-ride athletic scholarship is to compete in one of Division I’s head-count sports. An athlete who competes in one of the six head-count sports will either capture a full-ride or nothing. Here are the six sports and the total number of scholarships:

Men’s Sports

- Football (85 scholarships)

- Basketball (13 scholarships)

Women’s Sports

- Basketball (15 scholarships)

- Tennis (8 scholarships)

- Gymnastics (12 scholarships)

- Volleyball (12 scholarships)

In Division I men’s basketball, for instance, 13 athletes will capture a full-ride, and the other players are out of luck – they won’t receive any athletic money. That’s the rule whether you are a Division I basketball powerhouse like Duke and Kansas or below-the-radar schools like Nicholls State and Western Illinois universities.

Equivalency Sports

The NCAA considers all other collegiate athletic programs equivalency sports.

The NCAA dictates the maximum number of scholarships allowed per sport, but full-rides aren’t required. Unlike head-count sports, coaches in the equivalency sports can divide up their scholarships to attract as  many promising athletes as they can. Slicing and dicing scholarships often leads to meager awards. Small sports scholarships may only cover the cost of books!

many promising athletes as they can. Slicing and dicing scholarships often leads to meager awards. Small sports scholarships may only cover the cost of books!

In Division I men’s swimming/diving, for instance, there are a maximum of 9.9 equivalency scholarships. Division I women’s field hockey and lacrosse each have 12 equivalency scholarships. To attract more students, a coach with 10 scholarships might divide them up so that two-dozen students or more receive something. A top prospect, for example, might receive close to a full-ride, but that would leave less money for the coach to entice other recruits to the team.

Important: The vast majority of Division I sports teams do not offer the maximum amount of scholarship money permitted because they can’t afford the cost.

Athletic Scholarships by Sport

Here is the breakdown of the maximum Div. 1 and Div. II scholarships allowed by sport:

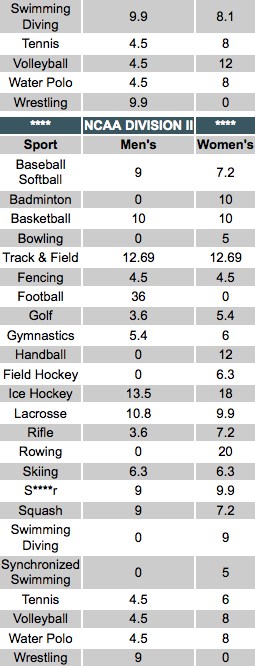

Breakdown of NCAA Schools

Three athletic divisions exist within the NCAA. Here is a snapshot:

Division I

Division I schools generally have the biggest student bodies, manage the largest athletics budgets and offer the largest number of scholarships. With nearly 350 colleges and universities in its membership, Division I schools field more than 6,000 athletic teams.

Division I is subdivided based on football sponsorship. Schools that participate in bowl games belong to the Football Bowl Subdivision. Those that participate in the NCAA-run football  championship belong to the Football Championship Subdivision. A third group doesn’t sponsor football at all. The subdivisions apply only to football; all other sports are considered simply Division I.

championship belong to the Football Championship Subdivision. A third group doesn’t sponsor football at all. The subdivisions apply only to football; all other sports are considered simply Division I.

Here is a list of Division I schools.

Division II

There are nearly 300 schools in Division II and they tend to be regional public universities and private universities. Division II programs can’t offer as many scholarships as Division I and all the athletic scholarships are classified as equivalency awards.

For example, a Division II football program can give out the equivalent of 36 full scholarships while Division I schools in the Football Bowl Subdivision can offer 85. Division II schools are prohibited from requiring their athletes to devote as much time to training as Division I schools.

Here is a list of Division II schools.

Division III

More than 170,000 student-athletes at 444 institutions make up Division III, the largest NCAA division both in number of participants and schools. Many of the schools in this division are private colleges and universities including many of the nation’s most elite schools. Prominent Division III schools include Washington University in St. Louis, Tufts University, University of Chicago, Amherst College and Pomona College. Exceptions are the Ivy League institutions that are in Division I, but they do not give out athletic scholarships.

Division III schools don’t provide athletic scholarships, but the vast majority of them give out merit scholarships, which are usually larger than athletic awards. It’s typically easier to get on a team in a Division III school than a Division I and the intensity of the programs aren’t as great. While  athletes at Division I schools are essentially employees of the institution, Division III athletes have the freedom to pursue other interests, to study abroad and to major in whatever they like.

athletes at Division I schools are essentially employees of the institution, Division III athletes have the freedom to pursue other interests, to study abroad and to major in whatever they like.

Here is a list of Division III schools.

Other Sources of Athletic Scholarships

National Association of Intercollegiate Athletics

Outside the NCAA, nearly 300 colleges and universities are members of the lesser-known National Association of Intercollegiate Athletics (NAIA). The vast majority of NAIA institutions are smaller private schools, which offer athletic scholarships.

Here is a list of NAIA schools.

National Junior College Athletic Association

The National Junior College Athletic Association is an association of community college and junior college athletic departments throughout the United States. Many of the schools in the NJCAA, which are divided into divisions, offer athletic scholarships. California state community colleges are not in the NJCAA and have their own organization, California Community College Athletic Association. Public community colleges in California are not allowed to offer athletic scholarships.

Here are the lists of Division I schools, Division II schools and Division III schools within the NJCAA.

Average Athletic Scholarship Amounts

A wonderful source for statistics on athletic scholarships is ScholarshipStats.com. In this chart below from ScholarshipStats.com, you can see that the average scholarship amounts are significantly smaller outside of Division I programs for men and women.

Also on ScholarshipsStats.com, you can check what the average athletic scholarships are at individual Division I schools throughout the country. Below I share a screenshot of the schools at the top of the list.

Know Academic Qualifications

If your son or daughter is interested in competing in Division I or Division II, he or she must register with the NCAA Eligibility Center. There are academic requirements to be eligible to play in these two divisions. You can’t play in Division I or II sports or receive a scholarship without registering and being cleared to play. A website called CollegeSportsScholarships.com provides a good explanation of the NCAA Eligibility Center.

Here is further information from the NCAA itself:

- NCAA Eligibility Center Quick Reference Guide for Division I

- NCAA Eligibility Center Quick Reference Guide for Division II

Be Realistic About Athletic Abilities

Parents often overestimate their teenagers’ athletic abilities. When students aim too high, they will be wasting their time. It’s easier to judge whether a child has a realistic change of playing at the various collegiate levels when it’s a timed sport like swimming and track and field. Students and parents need to do their research to determine what athletic abilities it takes to play in a particular sport in college.

Here is an example from AthleticScholarships.com, a recruiting site, of what it takes for a male soccer player to be an attractive prospect at each of the three divisions:

Don’t Wait to Be Discovered

Except for the true superstars – and there aren’t many of them – teenagers can’t wait to be discovered. Student athletes often believe that they will be discovered if they compete at showcases or tournaments, but that’s often not the case.

Students should reach out to coaches on their own. NCAA rules generally prohibit coaches from contacting a high school student directly before July 1 between their junior and senior year in high school. A few sports have different start dates. Teenagers, however, can contact coaches at any time.

Club and high school coaches can also act as an intermediary. A college football coach, for instance, might ask a high school coach to let a talented wide receiver, who is a freshman, know that he’d like to talk to him.

Teens who are interested in Division I sports, should consider reaching out to coaches no later than their sophomore year. Students should initially express their interest in an email. Here is what the email should include:

- Name

- Sport position

- Sports highlights/awards

- Available sports statistics

- Relevant physical characteristics

- Year of high school graduation

- High school name

- Contact information for high school and club coaches.

When coaches express interest, a student should make sure to periodically update them.

Create Some Buzz

A great way that students can boost interest among coaches is to create an online athletic profile. The majority of college coaches say that their recruiting process starts online. There are many online recruiting sites where students can create a profile for free or for very little cost. Students can then send coaches links to their sites. Information you should include in your materials would be such things as a bio, relevant sports stats, coach recommendations, upcoming game schedule and video clips.

Riki-Ann Serrins, a former women’s soccer coach at Georgetown and Tulane, once told me that coaches typically only need to see seven to eight minutes of action. The video clip doesn’t have to be a professionally done. In fact, Serrins suggests you can even use your phone to record it. You can upload your video on YouTube or a recruiting site and then send coaches the link.

Don’t Believe Everything Coaches Say

Coaches may tell teenagers that they have lots of scholarship money to divvy out, but prospects shouldn’t assume that they will be the recipients. I received this advice once when I interviewed Karen Weaver, who is a member of the sports management faculty at Drexel University, a television sports broadcaster and a former field hockey coach at several schools including Williams College and Ohio State.

A coach might not know whether he wants a particular athlete until he finds out what other prospects want to his team. What really matters is the scholarship amount contained in the school’s official athletic grant-in-aid form. “Until you get the grant-in-aid form, it’s meaningless,” said Weaver, who is a former national championship Division I field hockey coach.

Also keep in mind that a coach’s verbal commitment to an athlete is MEANINGLESS. Among highly competitive programs, some coaches are now offering verbal commitments to talented kids as young as middle schoolers, but there is absolutely no guarantee that a child who verbally commits to a team will end up on it. A coach can change his mind about a prospect and so could the child who couldn’t possibly know what he or she wants when that young.

The New York Times published the following front-page article regarding the collegiate recruiting of younger children:

Committing to Play for a College: Then Starting 9th Grade

I liked the blog post that someone at AthleticScholarships.com, a recruiting site, published in reaction to the outrage generated by the NYT article:

Criticism for Early Recruiting Missing the Mark

Athleticism can be a hook

Being an athlete can boost a teenager’s admission chances because all schools, regardless of whether they offer scholarships, desire strong sports programs. Your child doesn’t have to be a superstar athlete to increase his or her chances of admission. And your child doesn’t need to capture a sports scholarship to ultimately make your college tab more affordable.

Being a gifted jock dramatically improves your child’s odds of getting into some of the nation’s most elite colleges. At Ivy League schools, recruited sports candidates are four times more likely than other applicants to be accepted, according to Reclaiming the Game: College Sports and Educational Values, a book co-authored by William G. Bowen, a past president of Princeton University. Robert Malekoff, a former associate athletic director at Harvard University and a past women’s soccer coach at Princeton, concurs. Sports give students an admissions edge at other highly selective schools, too, he told me. “There is no question that there is an admission advantage for students who play sports,” Malekoff says.

You should never discount the level of competition between elite schools and their athletic departments, says Ellen Staurowsky, professor and program director of sports management at Drexel. “Even though there are no formal athletic scholarships, there is always a feeling that another institution may be out-recruiting yours because they are more generous about giving assistance.”

Understand that Athleticism Won’t Make Up for Poor Grades

A downside of focusing on sports scholarships is that it encourages students to spend more time on their sport than their grades. Kris Hinz, an independent college counselor, once shared with me her experience with high school athletes that nicely sums up the problem. Here is her observation:

In my practice, parents often apologize about their kid’s grades, then quickly say, “But he’s a great athlete and we’re hoping that can be his ace in the hole.” They are hoping that his athletic prowess will get him accepted and get him money! A tall order! They are usually wrong on both counts. And the worst part is, all the time that has been devoted to sports has siphoned off time that could have been spend studying to earn a strong GPA.

Division I Athletics Could Impact Your Child’s Major

Is your teenager hoping to major in premed or engineering?

Athletes competing in Division I sports won’t always get the chance. Division I athletics can be so time consuming that students can’t always major in a science, engineering or in other time-intensive fields. One survey indicated that one out of five athletes don’t major in their first academic choice. A few years ago, a USA Today investigation at 142 institutions with top sports programs revealed that many of the athletes participating in football, baseball, softball, and basketball programs were clustered into certain majors. For instance, 82% of the juniors and seniors on Georgia Tech’s football team shared the same major — management.

Some schools push students to select majors that aren’t as intensive, such as sociology and interdisciplinary studies. At the University of Nevada at Las Vegas, some athletes major in “university studies.”

Here is an article that focuses on the time issue for athletes: Do College Athletes Have Time to Be Students?

Look for academic fit first

Families often end up shopping for athletic scholarships rather than looking for schools that represent good academic fits. I’d recommend that you first identify schools that would be a match academically and then inquire about the sports. Getting a college education is obviously more important than playing a sport.

That’s the route we took when my daughter Caitlin, a soccer player, was looking at liberal arts colleges, which were all Division III schools. When we visited the schools, we made sure that we also visited with each soccer coach.

Five years out of college, Caitlin continues to love and play soccer in San Diego sometimes on multiple teams in a season. She was even approached by a semi-pro soccer team about playing, but she’s too busy for that. I assume that soccer will be a lifetime passion for her.

Athletic Recruiting

To learn more about the recruiting process, I talked with Avi Stopper, a former college athlete and a co-founder of CaptainU, which could be called an athletic LinkedIn that helps student athletes to connect with athletic coaches.

Stopper, who is a former men’s soccer coach at the University of Chicago, launched CaptainU when he was in the school’s MBA program. Over the years, hundreds of thousands of high school athletes, college coaches, youth coaches, and events have used CaptainU to get organized, promote themselves, and get noticed by others in the youth and college sports world.

Here are a few of Stopper’s main take-home points during the interview.

Rather than focusing upfront on athletic scholarships, student-athletes need to look for schools that would be good fits academically and socially.

Students should ask themselves this question: If I broke my leg and couldn’t play my sport anymore, would this be a school I’d want to attend?

A student shouldn’t bring up an athletic scholarship right when meeting or exchanging emails with a coach. That’s a turn off. The teenager needs to know more about the program and the coach needs to know more about the athlete before scholarships are broached.

Students should not ignore Division III schools even though they don’t offer athletic scholarships. Merit scholarships and financial aid from Division III schools often exceed what many students will get from athletic scholarships.

Top players are on Division I teams, but as you start to move down the Division I ranks, there is a lot more parody between some mid-tier Division I teams and some of the top Division II and Division III teams.

During our conversation, Stopper suggested that parents and student athletes should read a sobering 2008 story that ran in The New York Times regarding athletic scholarships. Here is the link: Expectations Lose to Reality of Sports Scholarships

Guides for Individual Sports

Here are some resources for specific collegiate sports. I’d like to add to this list! Please share any helpful websites about individual sports below!

Hi Lynn,

I’ve read that Ivy League schools do not give athletic scholarships (and most don’t give merit either?). However, I have heard stories from people who say “I know someone who went to Princeton (or other Ivy) and got $$ to play X sport.” In these cases is it most likely that those telling the story are misinformed and the student-athlete received need-based aid?

Also, is it possible that Ivy League schools, since they use the CSS/Profile form, may calculate need differently for different students. For example, they may use a more generous formula when calculating need for a highly desirable athlete? Just curious.

Thanks!

Kristin

Author

Hi Kristin,

The Ivy League gives zero athletic scholarships. There is no exception. People would prefer to say that their kid got an athletic scholarship from one of these schools rather than saying they qualified for need-based financial aid. And maybe the parents didn’t know. What you suggested in terms of an Ivy League school using a more generous formula for an athlete would violate NCAA rules.

Lynn O.

Thanks Lynn,

And are there any Ivy League schools that give merit aid?

Author

No there are no Ivy League schools that provide merit scholarships.

Lynn O.

Hi Lynn,

For NCAA schools where the NCAA specifies how many scholarships a school is allowed to give out, who funds these scholarships? Are they 100% school-funded? Does the NCAA fund a portion of the scholarships?

Thanks,

Kristin

Author

Hi Kristin,

The NCAA does not fund any portion of the athletic scholarships. The schools must fund these scholarships and many times the programs are not fully funded.

Lynn O.

Can’t find the transcript of the CaptainU interview & the link isn’t working.

Hi Heather,

Unfortunately, the recording source that I used (Spreecast) recently announced it was going out of business. So it’s no longer available to me either.

Lynn O’Shaughnessy